AI is shifting from experimentation to production infrastructure. When AI becomes core to a roadmap, unplanned GPU scarcity is no longer an acceptable failure mode. Enterprises are responding by acquiring GPUs and building private GPU clouds: shared infrastructure where the organization owns the queue, decides who gets GPUs, when, under what governance, and with what security posture.

This distinction is critical and increasingly supported by market signals and M&A activity. Crunchbase News reports that AI investment has shifted away from model novelty and toward infrastructure. In its analysis of recent AI driven acquisitions, the trend is summarized clearly: “The most aggressive buyers in AI are no longer chasing novelty. They are chasing infrastructure. As AI shifts from lab to production, the real battle is not about building models. It is about running them at scale, reliably and securely.”

This paper focuses on a specific second-order effect: once GPUs are owned, developers still expect cloud-like experiences. In practice, Kubernetes becomes the control plane for these environments, providing scheduling, isolation, and a uniform API surface across heterogeneous GPU hardware. Kubernetes is no longer optional infrastructure glue; it is the layer that turns raw GPU capacity into a consumable internal service.

Without a Kubernetes-based platform, bare metal GPU fleets become underutilized, politically contentious, and operationally fragile. Cloud-like developer experience on bare metal is becoming a platform requirement, not a luxury.

Section 1: Buying GPUs is now strategic and often economical

Big enterprises are buying GPUs (and also purchasing items like DGX systems, DGX SuperPODs, HPE Private Cloud AI, colocation clusters, etc.) because AI has transformed GPU compute into a production bottleneck and a strategic asset, not just “some servers you rent.”

There are few separate things that often get blended:

1.1 Guaranteed capacity becomes a roadmap dependency

When AI is a core product feature or a core operational capability, capacity becomes a first-class risk. The GPU ecosystem is already reflecting this: multi-year capacity agreements and specialized GPU providers exist largely because demand is spiky and supply is constrained. A private GPU cloud is a governance decision as much as a technical one: it is a way to own the queue and allocate GPU time to the highest ROI work.

The key is not infinite capacity, but predictability: developers should know when GPUs will be available and be able to plan work around clear, policy-driven queues.

1.2 A concrete cost curve: single-server breakeven example (8x H100 class)

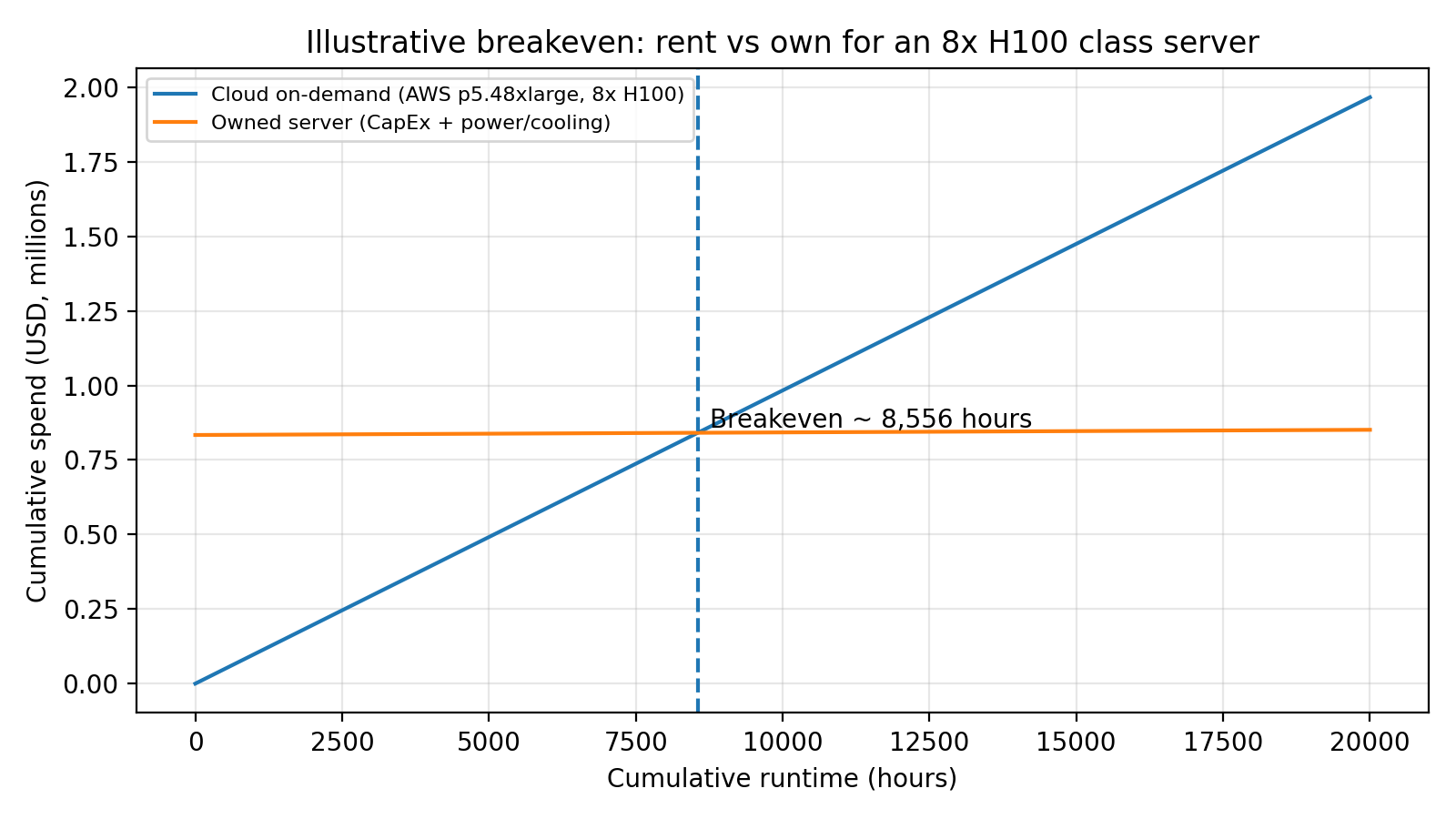

Cloud is excellent for speed and experimentation, but for predictable, sustained usage, renting can become the premium option. Lenovo Press published an illustrative total cost of ownership comparison using an 8x NVIDIA H100 server class and the closest AWS equivalent (p5.48xlarge). Their example includes explicit assumptions for hourly cloud cost, on-prem purchase price, and power plus cooling, and computes a breakeven in hours of runtime.

Figure 1. Illustrative breakeven curve for renting vs owning an 8x H100 class server (using Lenovo Press example inputs). Source: Lenovo Press TCO analysis.

1.3 Utilization thresholds: how many hours per day justify buying

In the same analysis, Lenovo Press also expresses the breakeven as a daily runtime threshold. This framing is useful in enterprises because it connects procurement decisions to workload reality: always-on inference, heavy fine-tuning pipelines, and large internal user bases can keep GPUs busy most of the day.

Figure 2. Illustrative daily runtime threshold to justify owning vs renting (same 8x H100 class example). Source: Lenovo Press.

1.4 Cluster-scale economics: why utilization determines outcomes

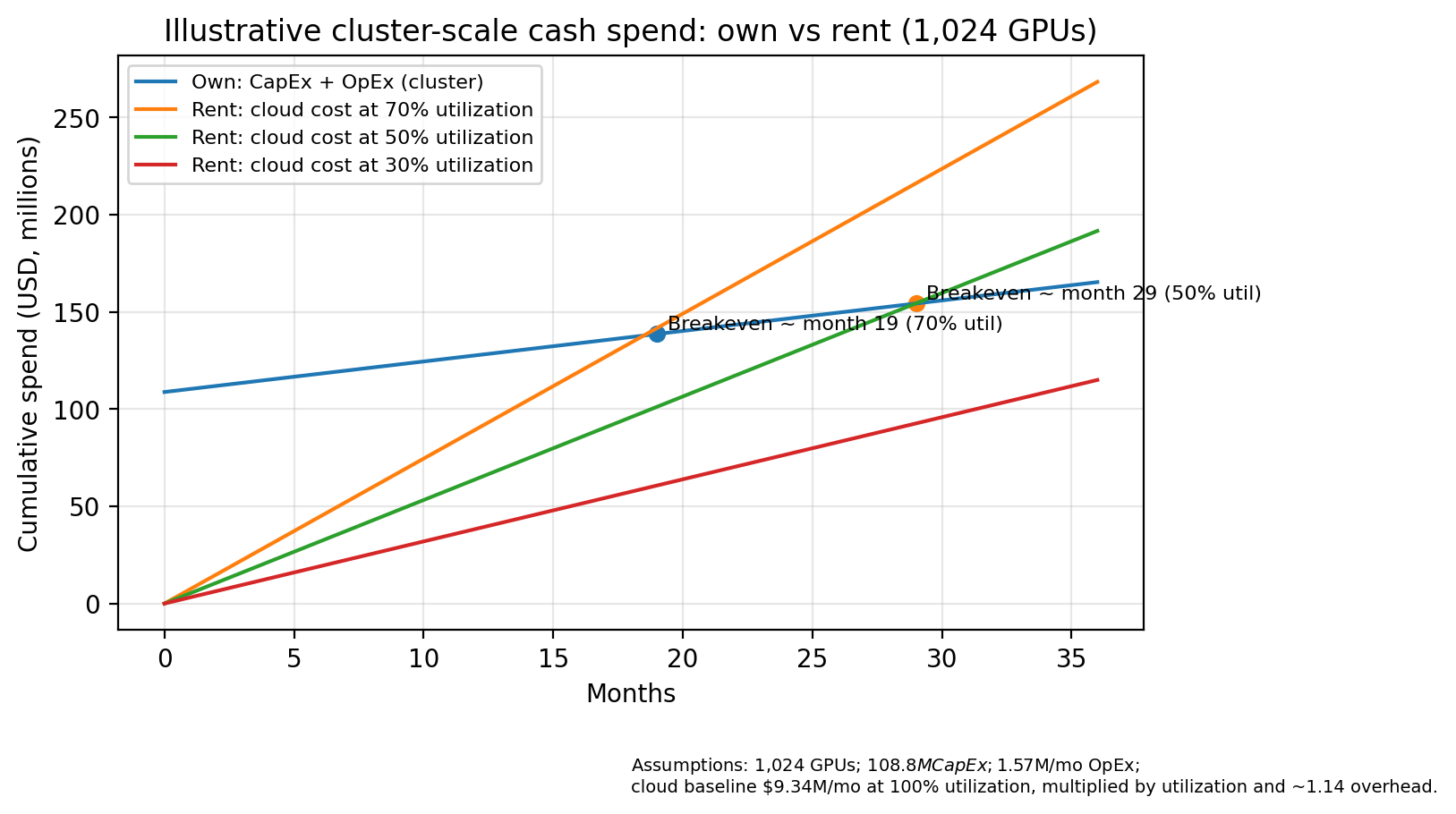

At cluster scale, the economics of owning versus renting GPUs are dominated by utilization rather than list prices. Owned infrastructure concentrates spend into a large month‑0 capital spike with a relatively shallow operating slope, while cloud spend is almost entirely operating expense that scales linearly with runtime.

The economics become a utilization math problem. A representative illustrative scenario (1,024 GPUs) shows the classic enterprise tradeoff: owned infrastructure has a large month-0 capital spike with a shallow operating slope, while renting is mostly operating expense that scales with runtime. In the illustrative scenario below, owning becomes cheaper at about month 19 at 70 percent utilization, about month 29 at 50 percent utilization, and does not break even within 36 months at 30 percent utilization.

Figure 3. Illustrative cluster-scale cumulative spend for own vs rent across utilization levels (assumptions listed in table). Cloud line uses utilization scaling plus an illustrative overhead factor to align with the stated breakeven points.

For executive teams, this turns utilization into a board-level lever. Higher GPU utilization with strong team isolation is what separates “GPU spend as sunk cost” from “GPU spend as a competitive advantage.” Make GPUs work harder for the business by treating clusters not as hardware purchases, but as shared, governed capacity that must hit utilization targets to justify the investment.

1.5 Compliance, sovereignty, and jurisdictional risk

Sometimes it’s not just the cost, but also the details of the play. For regulated industries such as finance, healthcare, defense, critical infrastructure, and large multinationals, the core questions go beyond whether a cloud is secure:

- Where does the data physically reside?

- Who has administrative or operational access?

- Which legal jurisdictions could compel disclosure or access?

These concerns are driving growth in sovereign cloud and private cloud deployments specifically positioned for AI workloads. In many cases, enterprises want clear answers about residency, control planes, and legal exposure that are difficult to guarantee in shared public cloud environments.

1.6 Strategic control and bargaining power

Training and large-scale inference require moving and repeatedly accessing massive datasets. Once those datasets live in a single public cloud, the combination of workflow coupling, data gravity, and transfer costs can make multi-cloud architectures and clean exits economically painful. Owning a meaningful portion of your compute fundamentally changes vendor dynamics.

With internal capacity, enterprises can:

- Use public cloud where it excels, such as burst workloads, managed services, or global delivery

- Avoid being forced into large committed-spend contracts just to access acceptable pricing or capacity

- Credibly walk away from unfavorable economics or terms

Moreover, the biggest advantage is preserving ROI stability when cloud pricing shifts unexpectedly, since owning baseline compute insulates core workloads from unilateral price increases such as the recent roughly 15 percent AWS uplift, preventing sudden margin erosion or forced architectural changes

That optionality has real value at enterprise scale. It enables more balanced hybrid strategies and reduces long-term dependency on any single provider’s pricing or roadmap.

Section 2: Buying GPUs does not fix allocation problems. Ad hoc capacity breaks at scale

Initially, an ad hoc approach to GPUs appears sufficient. Teams acquire GPUs for specific workloads, use them as needed, and then repurpose them for different requirements. However, as more business units begin to rely on GPUs, this model quickly becomes difficult to manage.

Sharing GPU resources effectively requires mechanisms that ensure proper isolation, fairness, and efficiency, which ad hoc setups struggle to provide at scale.

2.1 Coarse allocation wastes capacity by default

In most environments, GPUs are scheduled as an integer resource with Kubernetes as a layer for both GPU and CPU operations. This makes it easy to request 1 GPU, but it is coarse for inference, evaluation, and experimentation workloads that only need a fraction of a modern accelerator. Google Cloud explicitly warns that Kubernetes allocates one full GPU per container even when the container only needs a fraction, which can lead to waste and cost overrun.

Multi-Instance GPU (MIG) is one way to address this by partitioning certain GPUs into multiple hardware-isolated slices; however, it’s a journey to support it in an ad hoc manner. You still need standardization across your entire stack for consolidated performance.

2.2 Sharing increases utilization, but can reduce isolation

To recover wasted capacity, teams often turn to GPU sharing. Common approaches include time slicing, device plugins that allow multiple pods to share a single GPU, or user space schedulers that multiplex workloads. These techniques can significantly increase utilization, especially for bursty inference and experimentation workloads.

However, the isolation model becomes the limiting factor. NVIDIA explicitly documents that time slicing trades away memory isolation and fault isolation compared to Multi Instance GPU. A misbehaving workload can exhaust memory, trigger out of memory errors, or impact latency for other tenants sharing the same device. In practice, this means that sharing is only safe when all workloads have similar trust, performance, and reliability requirements.

This creates an operational dilemma. Some workloads require strong isolation for production, regulatory, or customer facing reasons, while others can tolerate softer isolation to maximize utilization. Ad hoc setups typically force a single sharing model across the cluster, either sacrificing utilization by avoiding sharing altogether or sacrificing isolation by oversubscribing aggressively.

A more robust approach allows multiple isolation levels to coexist. Soft sharing can be used where appropriate to improve efficiency, while stronger isolation is enforced for sensitive workloads. When this is integrated with Kubernetes native constructs such as scheduling, quotas, and workload level isolation, teams can choose the right tradeoff per workload rather than per cluster. Without this flexibility, GPU sharing becomes a source of risk rather than an optimization.

2.3 Distributed training is a scheduling and topology problem, not just a GPU count problem

For large training runs and high-throughput inference, performance is not determined solely by GPU model or raw FLOPS. It depends on how the entire system is architected as a cluster.

Key factors include:

- Interconnect quality, such as InfiniBand-class networking and topology awareness

- Storage bandwidth and latency, especially for checkpointing and data loading

- Scheduler efficiency, ensuring GPUs stay fed and are not left idle

- Stability, with no noisy neighbors disrupting long-running jobs

- Enterprises building private GPU clouds are often optimizing for tokens per second per dollar, not peak theoretical performance.

Distributed training further amplifies this. Large jobs frequently require gang scheduling, where all pods start together, and topology-aware placement to minimize cross-node communication latency. As described in Kubeflow’s Volcano scheduler guidance, treating distributed training as a scheduling and topology problem is essential for predictable performance. This does not emerge automatically from ad hoc resource allocation. The entire stack must be designed as a cohesive cluster.

2.4 Multi-team shared clusters create control plane bottlenecks

Namespace-based multi-tenancy can work at a small scale, but Kubernetes explicitly documents that namespaces do not isolate non-namespaced resources such as CRDs, StorageClasses, admission webhooks, and API extensions.

Kubernetes treats these resources as cluster-scoped by design, meaning all tenants implicitly share and compete for the same control plane surface area.

As clusters grow and more teams ship operators and custom APIs, this shared control plane becomes a hard scaling limit. Platform teams are forced into an approval and coordination role for every cluster-scoped change, slowing down iteration and increasing operational risk.

Because namespace isolation fundamentally cannot solve this class of problems, Kubernetes itself calls out control plane virtualization as the mechanism to properly isolate non-namespaced resources when namespaces are insufficient.

2.5 Observability and chargeback become harder once you introduce sharing

Attribution matters in an enterprise setting because GPU time needs to be measurable and accountable. NVIDIA documents a concrete limitation: when GPU time-slicing is enabled, DCGM-Exporter does not support associating metrics to containers. This makes per-team reporting and chargeback harder precisely when clusters are shared most aggressively. Specifically, when using Namespaces-based simple isolation between different tenants, more restrictions are imposed.

2.6 Summary: why ad hoc GPU fleets become a business problem

Section 3: Platforms are required to scale AI from 10 GPUs to 1,000 GPUs

Enterprises are no longer just buying GPUs; they are building a Kubernetes‑native AI infrastructure platform that turns bare metal GPUs into a shared service for many teams. AI engineering is working with larger models, higher latency budgets, and bigger datasets than traditional ML, which pushes organizations toward larger GPU clusters and specialized teams who know how to operate them at scale.

A head of AI at a Fortune 500 company summarized the maturity gap bluntly: “My team knows how to work with 10 GPUs, but they do not know how to work with 1,000 GPUs.” That gap is not just about more hardware; it is about platformization: consistent APIs, predictable scheduling, and clear governance for scarce accelerators.

3.1 What a cloud-like developer experience means on bare metal

Cloud‑like does not mean infinite hardware; it means removing human ticket queues from the critical path and making GPU access predictable and governed.

For GPU platforms, different actors have distinct expectations:

- For developers and data scientists: a single, consistent way to request GPUs; clear queues and estimated start times; self‑service environments with well‑defined ownership boundaries; and straightforward access to logs, metrics, and artifacts without opening platform tickets.

- For platform and SRE teams: enforceable quotas and fair‑share policies; standardized GPU stack lifecycle management (drivers, operators, runtimes, device plugins); safe upgrade paths with limited blast radius; and the ability to keep utilization in target bands without sacrificing isolation guarantees.

A concrete user story is instructive: a data scientist should be able to submit a 64‑GPU distributed training job, see its place in the queue, and understand whether it will start in minutes or hours, all within policy and without coordinating with a platform administrator. For developers, this is the difference between “ticket queues and manual node allocation” and a simple mental model: GPUs when needed, with clear rules.

For platform teams, the goal is to make bare metal feel like policy‑driven, Kubernetes‑native self‑service while preserving the performance characteristics of the underlying hardware.

3.2 Kubernetes as the layer that changes the economics of owned GPUs

Buying GPUs only creates an asset; Kubernetes turns that asset into usable, governable capacity. At scale, the economic value of owned GPUs depends on having a single control plane that can schedule, isolate, and continuously rebalance workloads across the fleet.

Overall, this provides a layer that transforms bare metal GPUs into a shared pool with consistent semantics. Because GPUs are requested declaratively and scheduled centrally, utilization improvements come from policy and automation rather than human intervention.

Equally important, the most popular OSS container orchestrator standardizes the operational surface area. GPU drivers, device plugins, runtimes, and operators can be managed as part of a controlled lifecycle, reducing drift and limiting blast radius during upgrades. This allows platform teams to evolve the GPU stack without disrupting running workloads or forcing global maintenance windows.

At this point, Kubernetes is not just a container orchestrator; it is the economic control plane for owned GPU infrastructure. It is what converts a large capital investment into predictable, high-utilization shared capacity that can scale from tens to thousands of GPUs under clear governance.

The practical outcome is a single GPU platform that serves many independent teams, rather than a collection of siloed clusters that are difficult to govern and hard to keep utilized.

Section 4: Building platforms the right way: vCluster and vNode fit

A GPU platform must solve isolation, sharing, and lifecycle management in a way that scales across teams, but there is no single prescribed implementation. The approach closest to a native experience is to own the hardware and expose it through Kubernetes, allowing the platform to provision and allocate GPUs according to clear isolation boundaries while retaining near bare metal performance.

Crucially, a modern platform must also expose that capacity through fast, self-service APIs so that clusters and tenant environments can be created in seconds, GPU nodes can autoscale to match queues, and everything is expressed as code via Terraform and GitOps workflows.

4.1 Platform architecture patterns for multi-team GPU fleets

There is no single architecture for a private GPU cloud. Common patterns include a spectrum of designs that trade off isolation, utilization, and operational overhead, and most enterprises end up mixing several of these patterns in a single platform as they mature:

- Dedicated clusters per team: strong isolation and autonomy, but expensive and hard to keep utilized.

- Shared cluster with namespaces: simple and efficient, but constrained by cluster‑scoped resources and shared control plane blast radius.

- Virtual control planes per tenant: isolates control plane resources while still sharing underlying nodes.

- Hybrid fleets: own baseline capacity on‑prem or in colocation, then burst to hyperscalers or specialized GPU providers when demand spikes.

4.2 vCluster: virtual control planes aligned with Kubernetes guidance

Kubernetes identifies two primary options for sharing a cluster among multiple tenants: a namespace‑per‑tenant model and a virtualized control plane model, where each tenant receives a virtual control plane to isolate non‑namespaced, cluster‑scoped resources. The official guidance notes that control plane virtualization is a good option when namespace isolation is insufficient but dedicated clusters are undesirable.

vCluster implements this model by running a virtual Kubernetes control plane per tenant and syncing only a minimal set of low‑level resources (such as Pods and Nodes) into a host cluster for scheduling, which aligns with CNCF‑documented patterns for internal developer platforms that need strong control plane isolation without managing many physical clusters.

Unlike namespaces, which share a single control plane, or relying solely on cluster-per-team isolation, which can fragment capacity, virtual control planes let teams operate independently while drawing from the same GPU pool. When required, your tenancy spectrum can span Pools from different vendors and infrastructure without any overhead.

With vCluster, virtual clusters themselves can be provisioned in seconds, giving developers and platform teams a self-service path to new environments that feels faster than provisioning a new managed EKS cluster, which typically takes many minutes for control plane and node setup.

4.3 Multi‑cloud GPU management and elastic scaling

Once teams have independent Kubernetes control planes, elasticity becomes tractable. vCluster doesn’t just do control plane isolation. There’s more to the vCluster layer.

vCluster’s Auto Nodes capability extends Karpenter‑style just‑in‑time node provisioning to environments beyond managed public clouds, including bare metal and private AI clusters, so that worker nodes (including GPU nodes) can be created and destroyed on demand to match queues.

This supports a hybrid model where each tenant environment can scale up for training or evaluation spikes and then scale down to avoid idle capacity, across on‑prem fleets, colocation “GPU factories,” and hyperscaler or specialized GPU providers. Auto Nodes makes GPU autoscaling a first-class, policy-driven feature rather than a custom script or manual process.

4.4 Managing the Kubernetes compute layer with one platform

Node lifecycle is a core operational challenge in GPU environments: nodes must be provisioned, configured with the correct drivers and runtimes, drained safely, and wiped before reuse across teams. vCluster Private Nodes integrates with node providers, including NVIDIA Base Command Manager (BCM), to schedule specific bare metal nodes as worker nodes for a tenant vCluster and to invoke secure wipe and re‑provisioning workflows on deprovision.

Centralizing this lifecycle management enables organizations to treat GPU nodes as a shared pool that can be dynamically assigned to tenants with clear boundaries, rather than static, team‑owned hardware that drifts over time.

4.5 Integrations: BCM and Netris for bare metal lifecycle and network isolation

In bare metal GPU “factories,” the platform must manage both compute lifecycle and network isolation. The BCM node provider enables vCluster Platform to integrate with NVIDIA Base Command Manager to allocate, monitor, and recycle bare metal GPU nodes under a consistent policy, while the Netris integration provides network automation for vCluster control planes and their private nodes.

Using Netris, vCluster can provision isolated network paths, load‑balancing, and kube‑VIP configuration via Multus, replacing manual VLAN, ACL, and load balancer configuration with a declarative, cloud‑like network model suitable for multi‑tenant clusters.

4.6 vNode runtime: hardened isolation for shared‑node multi‑tenancy

Control plane isolation alone does not prevent node‑level breakout risks when multiple tenants share the same physical worker nodes. vNode is a multi‑tenancy container runtime that provides strong workload isolation by combining Linux user namespaces, seccomp filters, and other kernel‑level controls, while running at near‑native speed without a hypervisor.

vNode integrates via Kubernetes RuntimeClass, allowing platform teams to selectively apply hardened runtime isolation to specific tenant environments or workload classes that require stronger security or need to run privileged workflows safely, without incurring the overhead of placing every tenant into full virtual machines.

Section 5: Getting started. A practical roadmap

Before expanding GPU procurement, define workload classes that drive scheduling policy and isolation requirements. A simple taxonomy (training, batch fine‑tuning, always‑on inference, evaluation/experimentation) guides which workloads need dedicated nodes, which can share safely, and what latency or reliability constraints must be enforced.

In parallel, define governance primitives early: quota policy, identity and RBAC model, and approval boundaries for sensitive workloads, so platform behavior remains predictable as teams onboard.

5.1 Standardize the GPU foundation and node lifecycle

In most organizations, the fastest path to stability is a standardized GPU node baseline: consistent driver and container runtime management, a single GPU operator deployment strategy, and repeatable node labeling.

Automate upgrades in rings to reduce blast radius, and on bare metal, pair this with an explicit node lifecycle process that covers provisioning, validation, draining, and secure wiping before reuse across teams.

5.2 Add job-level queueing and fair-share scheduling

Introduce job‑level admission control and queueing so scarce accelerators behave like a shared service rather than a race condition. Kueue was created specifically to address gaps in plain Kubernetes, which lacks job‑level ordering and fair sharing for batch workloads; it adds APIs for elastic quotas, workload priorities, and FIFO or priority‑based queueing strategies that decide when jobs should start or wait.

For distributed training, integrate gang scheduling and topology‑aware placement using schedulers such as Volcano, ensuring all Pods in a training job start together and are placed with awareness of network topology to reduce communication latency. This is what turns a GPU fleet into one shared platform for many teams: GPUs continuously execute the highest‑value work instead of being fragmented across siloed clusters.

5.3 Roll out control plane isolation for teams

Once queueing, quotas, and baseline GPU observability are in place, introduce tenant‑level control plane isolation. This allows teams to manage their own CRDs, operators, and tooling stacks without requiring cluster‑admin involvement for every change, while the platform team maintains governance of the underlying GPU fleet.

vCluster Platform provides this control plane isolation in a Kubernetes‑native way: each team gets its own virtual Kubernetes control plane (vCluster) with isolated CRDs, operators, and policies, while sharing the same underlying GPU nodes. Platform teams can let tenants run their own operators and admission webhooks safely, limit the blast radius of misconfigurations to a single vCluster, and standardize guardrails (RBAC, quotas, network policies) at the host‑cluster level so every vCluster inherits consistent security and governance.

5.4 Add hardened runtime isolation with vNode where sharing is required

If the platform includes shared node pools, treat node‑level isolation as a first‑class concern. Introduce vNode selectively for tenant environments or workload classes that require stronger runtime isolation, such as workloads handling sensitive data or running privileged pipelines, so multiple tenants can safely share physical nodes without defaulting to a dedicated VM per tenant.

Combined with virtual control planes, this hardened runtime model lets many teams share GPU nodes without noisy‑neighbor or security nightmares, enabling “break things safely”: run risky experiments and privileged pipelines with strong isolation, without slowing down production work.

5.5 Integrate elastic scaling and network automation for private GPU clouds

As demand grows, shift from manual capacity planning to elastic provisioning across both on‑premises and public cloud environments. Node provider integrations in vCluster Platform, such as NVIDIA Base Command Manager, allocate and recycle bare metal GPU nodes safely, while network automation integrations like Netris ensure tenant environments receive isolated network paths without manual network configuration.

With these capabilities, each tenant can use Private Nodes for dedicated on‑prem capacity (including NVIDIA DGX BCM environments) and Auto Nodes for on‑demand burst into public clouds or specialized GPU providers when baseline capacity is exhausted, while keeping a consistent Kubernetes‑native workflow across locations.

5.6 Operationalize the platform: metrics, chargeback, and upgrades

Finally, close the loop with operational metrics. Track GPU utilization by pool, queue latency, job success rate, and environment provisioning time, and build internal chargeback or showback aligned to the scheduling and quota model.

Establish a predictable upgrade process for drivers, runtimes, and platform components so teams can move quickly without platform instability becoming the bottleneck, using staged rollout rings and clear SLOs for platform availability.

Section 6: Business outcomes for leadership

The outcome is a Kubernetes‑native AI infrastructure platform that provides a cloud‑like experience without cloud lock‑in, turning owned GPUs into governed, high‑utilization shared capacity rather than scattered one‑off purchases. In short: cloud experience without cloud lock-in, a Kubernetes-native AI infrastructure platform that runs like EKS, performs like bare metal, and makes GPUs work harder for the business.

With vCluster Platform and vNode this includes three specific capabilities that are often missing on bare metal compared to hyperscalers:

- Spin up clusters in seconds: virtual clusters and tenant environments are provisioned in seconds via APIs or Terraform, significantly faster than the many minutes typically required to provision new EKS control planes and attach worker nodes.

- Autoscale GPU nodes: Auto Nodes and node provider integrations dynamically add and remove GPU worker nodes across bare metal, colocation, and cloud providers, so GPU capacity expands and contracts with job queues instead of being statically allocated.

- Automate with Terraform & GitOps: vCluster integrates with Terraform modules and GitOps tooling such as Argo CD or Flux, so teams can declare virtual clusters, node pools, and policies as code and treat GPUs like any other infrastructure resource in their pipelines.

For leadership, this translates into:

- Higher ROI on GPU investments through consistently higher utilization.

- Smarter capacity planning with hybrid-ready elasticity instead of overbuying.

- Fewer incidents and outages from noisy neighbors or ad hoc changes.

- Faster experimentation cycles and time-to-production for AI workloads, using the same Terraform and GitOps workflows already standard in the organization.

Moreover, as organizations move from early experiments to mature, multi-team AI platforms, their architecture typically evolves across this spectrum: starting with single shared clusters, adding virtual control planes, and eventually operating hybrid on‑prem and cloud fleets. vCluster is designed to follow this journey, supporting dedicated clusters, namespace-only setups, virtual control planes, and hybrid or multi-cloud topologies under one control plane so platform teams do not have to replatform when requirements change.

If you’re interested in how to optimally utilize GPUs in Private Cloud or want to see reference case studies, feel free to connect here.

Deploy your first virtual cluster today.